C. elegans is a nematode, typically about 1 millimetre long, and found in soil all over the world. These neat little creatures were the first animal to have their entire genome sequenced (they were the test run for the Human Genome Project). They are one of a handful of “model organisms”: species that scientists know a heck of a lot about because many, many researchers around the world choose to study them. You can learn more about C. elegans and the first scientists who studied them in this super book.

I spent a year studying the swimming dynamics of C. elegans with Dr. Kari Dalnoki-Veress and the worm team: Dr. Matilda Backholm and Rafael Schulman. My research consisted of catching worms by the tail using a glass tube thinner than a human hair while looking through a microscope and applying suction with a big syringe. This technique, coined micropipette deflection and developed in Kari’s lab, allows us to measure the nano-scale forces the worm exerts while swimming.

My project investigated the effect of viscosity on the swimming dynamics of the worms. Image analysis allowed us to track the motion of the worm and measure the amplitude and frequency of swimming.

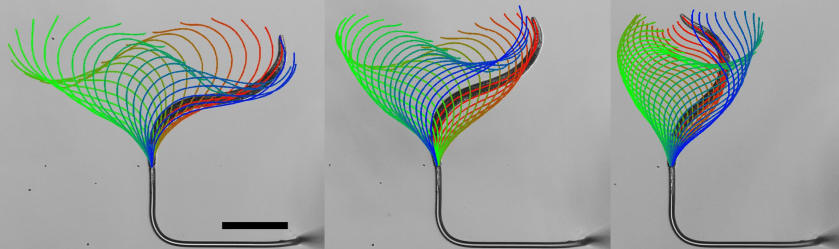

The same worm in 3 different viscosities, increasing viscosity left to right. Scale bar is 200 μm.

The coloured lines show the position of the worm over one cycle of swimming, with time swept out as the colour transitions from red to green to blue. As viscosity increased, swimming became slower and lower amplitude. By measuring the forces of the swimming worm, we were able to determine the power output. We found that C. elegans maintains a constant power output in changing conditions, indicating the worm adjusts its gait to keep a constant rate of energy consumption. Pretty smart – for a worm with only 302 neurons.

Check out the full paper here.